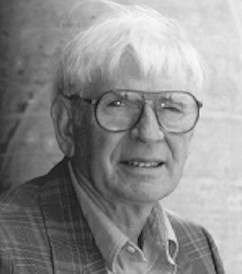

Douglas E. Ryan

Recollections and Reminiscences

By Douglas E. Ryan

We arrived in Halifax from London in August of 1951. I had just received my PhD from Imperial College and had been hired as an Assistant Professor at the princely salary of $3,000 per annum. My stipend in London (on a Beaverbrook Overseas Scholarship) had been £650/yr and $3,000 seemed pretty good; it was reluctantly increased to $3,300/yr by then President A.E. Kerr shortly after term began.

Ã˝

The Studley campus (where the Science Building was located) was quite lovely; the photographs below show the campus in 1940 and 1983. In 1951 there was a pre-fab, built during the war, between the law building and gymnasium and the Arts and Administration Building had just been completed. Much of the campus was open green space with lots of trees. An unpavedÃ˝road, lined on both sides by beautiful trees, ran from the corner of Coburg and Lemarchant streets to the back of the Science Building.Ã˝ A stream flowed through the campus where Walter Chute would rinse out the acid baths before we all became more environmentally aware.

|

| ¬È∂π¥´√Ω campus circa 1940. |

The department consisted of Carl Coffin, Walter Chute, Walt Trost and myself. Carl, who was head of the department, was an innovative experimentalist and encouraged staff to maintain research programs in addition to their teaching responsibilities. Carl‚Äôs sight had been seriously impairedÃ˝ in a lab accident in 1948 and one of my jobs was to run Carl‚Äôs Chemistry 2 lab of inorganic chemistry and qualitative analysis (I also taught Chemistry 7 (quantitative analysis) and a graduate class).

|

| The campus has filled in quite a bit as shown in this photo circa 1983. |

What I most remember about the Chemistry 2 lab is that we used cylinders of hydrogen sulphide (kept in the fume hood) in the separations;Ã˝ despite warnings of do not put your head in the fume hoodÃ˝when saturating solutions with hydrogen sulphide,Ã˝every lab day at least one person would keel over at the fume hood and would have to be dragged out into the fresh air to recover. It‚Äôs no wonder I turned gray early. Carl taught Physical, Walter taughtÃ˝Organic, Walt, Inorganic and I, Analytical Chemistry (primarily in our fields of training) but there was considerable overlap of teaching areas; Walt, for example, gave the introductory chemistry class, Chemistry 8 plus orbital theory, Carl ‚Äì Chemistry 5 plus thermodynamics and Walter ‚Äì Chemistry 4 and 6, but we all did graduate classes in whatever area seemed necessary at the time.

|

| The cupola hid an air-raid siren. |

The cupola on top of the science building (shared by physics and chemistry) housed an air raid siren which blasted off at least once a week. The room in which I lectured was directly under the cupola and when the siren sounded you would swear the building was in the throes of collapse. It normally went off at 11 a.m. but the damn thing would catch us off guard every time and the entire class would jump about two feet. Another reason why I turned gray early.

I had labs fiveÃ˝afternoons a week and a Saturday morning lab. There were no demonstrators and we did it ourselves with a little help from a man in the stockroom. It sounds incredible now but I then think of my undergraduate years at UNB where Frank Toole and Bobby Wright taught all the classes in chemistry and managed to do a very good job of it; I believe we did too. We managed to do some research but could give it limited time during school terms; our graduate students kept things going during term and we looked forwardÃ˝ to the breaks to catch up. I hadÃ˝two graduate students (Graeme Cheney and Gerry Lutwick) in my first year and both went on to get their PhDs elsewhere after receiving their M.Scs. It wasn‚Äôt until 1960 that the department was given the right to offer the PhD and many a university in Canada and elsewhere benefited from graduates produced by our department and other Maritime institutions. Even after we were giving Ph.Ds we encouragedÃ˝ graduates who had received both their bachelor and master degrees with us to broaden their horizons and go elsewhere for their doctorates; good for them but not so good for us.

Salaries were not great at ¬È∂π¥´√Ω in my early years and I supplemented earnings by doing analyses for different people or organizations. I continued to do this for a number ofÃ˝ years until I learned that Ron Hayes (Head of the Biology Dept.) had advised someone to ‚Äútake it to Doug Ryan, he‚Äôll do anything for money‚Äù. As an example, the Public Service Commission sent me a colorimeter and filters being used to monitor the fluoride now being added to the Halifax water supply; it was supposed to be no greater than 1 ppm. I found that the system was reliable up to 1ppm but unreliable above; it gave the same reading at 2ppm as it did at 1ppm. I told them it could easily be checked by simply diluting with distilled water and measuring again. I charged $50 and ultimately received a cheque with no covering letter or thank you. Another example of our naivety in what to charge for a provided service comes from Walt Trost who was asked to come down to the waterfront to advise on a fire that had damaged a ship; accompanied by a lawyer Walt did his examination, gave his opinion and, when asked his fee, said $50.Ã˝The lawyer looked at him pityingly, reached into his pocket and pulled out a $50 bill; Walt then realized he should have said $500 for his opinion to have any value. These were lessons we learned the hard way but $50 wasÃ˝a lot to us at the time.

I should clarify my comment about salaries.Ã˝Several years after my arrival at ¬È∂π¥´√Ω I had a letter from Martin Kilpatrick, Head of the Chemistry Dept. at the Illinois Institute of Technology in Chicago, asking if I would like to return as Assistant Professor. I had spent a year there as an instructor prior to London and it had a number of first-rate men; for example, Harry Gunning was there (later became head ofÃ˝ the Chemistry Dept. at the University of Alberta) as was Dick Bernstein (who became one of the top U.S. scientists). Dick and I shared an office and were good friends. I don‚Äôt remember what my salary actually was at the time but it was more than Kilpatrick was offering and salaries at ¬È∂π¥´√Ω didn‚Äôt look so bad in comparison.Ã˝Ã˝Ã˝Ã˝Ã˝Ã˝Ã˝Ã˝Ã˝Ã˝Ã˝Ã˝Ã˝Ã˝Ã˝Ã˝Ã˝Ã˝Ã˝Ã˝Ã˝Ã˝Ã˝Ã˝Ã˝Ã˝Ã˝

We first lived in a small apartment in a row ofÃ˝three brick town houses on Jubilee Road; there were four of us (Nan, our son who was now 4¬Ω, a large golden retriever and myself). One day, as Gerry Lutwick and I were working in the lab, Gerry asked where we lived; when I told him 85 Jubilee Road he exclaimed ‚Äúbut that‚Äôs a well-known address to many of the young men around town!‚Äù The apartment upstairs was rented by several young women who were pleasant and never gave us any trouble but I soon learned simply to say, when our doorbell rang in the middle of the night, ‚Äúupstairs‚Äù. In February of 1952 Michelle was born and a larger apartment became necessary. The university owned a house at 198 University Avenue (given to them by Dr. Bronson, a former member of the physics dept) and we were lucky to be able to move into the upper flat. George Grant (Philosophy) occupied the flat below. It was a lovely large apartment but when the university decided to raise the rent (and banks or trust companies were only too happy to loan money to young ¬È∂π¥´√Ω faculty) we bought a house on the St.Margaret‚Äôs Bay Road in Armdale; several other faculty lived in the same area.

My first office was on the third floor of the science building; it had a door which opened into the physics part of the building. Ernie Guptill, Keith Hoyt and Alex MacDonald were younger members of the physics department; Bill Archibald and Jack Johnstone were more senior. The younger members would gather in my office for our brown-bag lunches and had great discussions (not usually having anything to do with the university). One of the favorite topics was penny stocks which I knew nothing about; no one lost or gained much but it was great fun. Ernie lived just up the Bay Road from me. We would often meet at the bus stop on Quinpool Road and throw rocks, while we waited, at the rats which abounded where a stream and sewer outlet emptied into the Northwest Arm (we walked through a field and over a small bridge to get to the bus stop). One time while pacing prior to going into my first lecture at the beginning of term I asked Dr. Johnstone, ‚ÄúHow long is it before one gets over being nervous at the beginning of term? ‚Äú He placed his hand on my shoulder and replied, ‚ÄúMy boy one never does‚Äù.Ã˝ He was right!

Carl died in January of 1954 and Walter Chute became Head of the Department. Brian Dunford was appointedÃ˝Assistant Professor in 1955 to fill the gap left by Carl‚Äôs passing but returned to the University of Alberta, where he had obtained his BSc and MSc degrees, in 1957. Walt went on sabbatical in 1957-58 and Russ Webber was appointed as Assistant Professor; Russ left in 1962 for Sir George Williams University. Gerry Dauphinee (MSc 1953) arrived from the University of Toronto in 1958 and was an important addition while Walt was on sabbatical and for many years thereafter; Gerry became Assistant and then Associate Professor in 1971.

The university was growing and the department with it. While the addition of new staff removed some of the load, we all became involved in planning (physics moved into the new Sir James Dunn Science Building in 1960 and we took over the space occupied by them). The department obtained the right to offer the PhD in 1960; physics and chemistry were the first two individual departments granted this right.Ã˝St. John Blakeley (MSc. Imperial College, London) received the first chemistry doctorate in 1964 for a thesis on Heterometry. I went on sabbatical in 1959-60 and much of the remodeling had been done when I returned.

The department continued to expand in the sixties. Ten new staff members were added, weÃ˝ underwent another extension (the Chemistry Building was connected to the Macdonald Library), and a new Honours program was initiated in 1966-67. I was becoming restless in the early sixtiesÃ˝and debated whether I wanted to stay at ¬È∂π¥´√Ω or not. The University of Guelph was looking for a departmental chairman and I went to be interviewed (along with I don‚Äôt know how many others); I received a letter shortly after my return to Dal offering a position as full Professor (I was Associate Professor in my own dept. at the time). However, I was made McLeod ProfessorÃ˝ in 1963 and stayed until retirement.

Kelly was born in 1961 and we purchased a five-bedroom house on Henry Street just around the corner from our first flat on Jubilee Road; it had a very large living room separated from the dining room by sliding doors. It was an ideal place to entertain and we used to have large buffet parties in addition to more intimate sit-at-the-table ones. There could be as many asÃ˝50 for dinner and it was all prepared by my wife without help except for clean-up in the kitchen; this was done by our teenage daughter and a friend. We didn‚Äôt have a dishwasher and I only learned recently that the girls would drink the remains in the glasses before washing them.

Walt Trost left the department in 1961 to become Dean of Graduate Studies and in 1966 became Academic Vice-President at the University of Calgary. Walt and I had become great friends over the 15 years we had been together at ¬È∂π¥´√Ω and it was a sad day when he left. Henry Hicks was made President in 1963 and was a constant source of support after I became chairman in 1969. The university had decided to change from heads to rotating chair persons in 1969 so Walter Chute went on sabbatical and I became chairman. It was a good time to be chairman since the university continued to grow and support monies were available if reasonable arguments were made.

We had written and produced laboratory manuals for our classes for years and were turning out quite professional looking ones by now; these went to the university book store for sale but no money came back to the department. I decided, therefore, that we would sell the books in the department and keep the money to establish a departmental account for uses other than academic. The book store wasn’t happy and it put an additional burden on the office at a busy time of the year but it gave us a freedom that we hadn’t had before.

The National Research Council’s granting body had introduced Negotiated Development Grants to support new research initiatives and we submitted a proposal to establish a Trace Analysis Research Centre (TARC); such proposals had to have the backing (and what turned out to be considerable financial support) of the university. President Hicks was at first skeptical and said it would reflect badly on the university if it was unsuccessful (he knew that very few were funded) but I argued that this would not be so if we submitted a good application. We were awarded a grant of $359,000; this was a lot of money in 1971 and made many things possible not only for the analytical chemists but also for the department as a whole. We were able to bring in new staff, purchase much needed equipment, support postdoctoral fellows and to add additional personnel so necessary to a growing department; the university‘s commitment was to take over support as the grant money ran out. There were other commitments, however; there was no space for the new centre in the Chemistry Building so we were given a house on University Avenue which had already been converted for a laboratory discipline. When we left for lovely new quarters on the top floor of the Life Sciences Building, the house remained for the use of chemistry for several years. I should emphasize that staff being added to TARC were departmental members and were told that their first commitment was to the department; TARC was simply a vehicle to obtain research monies from granting bodies. Chatt, a nuclear chemist, was the last man to be hired through the Negotiated Development Grant money.

Ten new departmental members were added from 1970 to 1976 and we were being recognized both nationally and internationally for the research being done in the department; individuals were members of granting bodies, editors of scientific journals or on editorial boards and were invited speakers at international conferences. It was the natural progression of things but I would sometimes give new faculty a copy of a paper titled “Who killed Cock Robin?” It described the meteoric rise of a young scientist (because of the excellent papers he was publishing) who became so involved in committees, conferences etc. that he was no longer publishing anything worthwhile; people were then asking “Whatever happened to Cock Robin?”

I was appointed to an additional three-year term as Chairman in 1972 but it was necessary to devote more attention to the growth of TARC and I resigned as chairman on January 1, 1974.Ã˝ I moved to a new office in what was now the Trace Analysis Research Centre in the Life Sciences Building.

In the '70s I received a letter from Bob Jervis in Toronto to see if we had any interest in a Slowpoke Reactor (a small swimming pool reactor which was ideal for training in nuclear chemistry and for neutron activation analysis); he believed a proposal to establish a network of such reactors in universities across the country would be looked on favorably by the government. Chatt received his Ph.D. with Jervis and was a nuclear chemist but his research was limited without a reactor so of course we were interested. Many departments were interested but only four universities (Alberta, Toronto, Ecole Polytechnique and ¬È∂π¥´√Ω) would support an application; considerable support was required since a hole 20 ft. deep and 8 ft. in diameter would have to be drilled to contain the water for the reactor. Anyway, I became chairman of the universities reactor committee and proposals were sent to ¬È∂π¥´√Ω for forwarding; each proposal was individually defended before an Atomic Energy Control Board committee (I appeared for ¬È∂π¥´√Ω).We were granted $192,000 for the reactor but I have no idea what it cost the university for the installation; the reactor and attendant laboratories were given space in the basement of the Life Sciences Building. Chatt and I put together the ¬È∂π¥´√Ω application and I was named Slowpoke Director; Chatt, however, was instrumental in its success. It would be remiss of me not to mention Jiri (George) Holzbecher who earned his Ph.D. with me, became Principal Slowpoke Operator and was responsible for the day-to-day operation of the reactor; I don‚Äôt know what we would have done without him.

In 1979 Professor Ramakrishna, Head of the Chemistry Dept. at the University of Colombo in Sri Lanka, came to spend some time with me and we discussed the possibility of submitting a proposal to CIDA (Canadian International Development Agency) to establish a Centre for Analytical Research and Development (CARD)Ã˝in Colombo. There were no financial commitments by ¬È∂π¥´√Ω (apart from salaries already being paid to TARC staff), we were given the university‚Äôs blessing and submitted an application. In 1980-81 weÃ˝were awarded $461,000 with all finances to be handled through ¬È∂π¥´√Ω. I had gone to Colombo before submission of the grant application and went back to help them get started; other TARC members also went, at different times, to advise and help with equipment installation etc. The centre was a great success (we held a conference in 1984 with scientists from North America., Europe and Asia in attendance). Although there were rumbles of instability, there were no difficulties at the conference and we only became aware of the ethnic problems later in 1984. The president of the university, a supporter of the initial application to CIDA and of the centre, was assassinated and the University was closed. Tamils were fleeing the country (Ramakrishna among them) and that was the end of our CIDA project in Sri Lanka.

Other projects in which I was involved included: a linkage agreement in chemistry between ¬È∂π¥´√Ω and Dhaka (Bangladesh) Universities; an international meteorites project (an attempt to classify meteorites in which analysis plays a major role); and a Leishmaniasis study in Brazil (over 100 million people are affected by this parasitic disease and they still do not know what constitutes an effective dosage of the antimony used to control it (antimony is a virulent poison and enough must be added to kill the parasite yet cure the patient; the drug companies have made little effort to come up with a cure since there is little profit to be made from warm poor countries where the parasite thrives).

I have said nothing about the chemistry classes I taught and teaching is, after all, the first responsibility of the university. I enjoyed teaching, particularly the large first and second year classes; I suppose this was because they made me feel young. I had good rapport with the students and over the years received notes, cards, poems and even a cake (presented before the class on Valentine’s day). I will end this R and R with the only poem I kept because I thought it was so clever.

We walk into our class each day,

Set down our books, sit on our chairs,

Sharpen our minds in that we may

Stepwise, ascend knowledge-stairs.

In he walks! The stalking lair

In which eternal wisdom dwells,Ã˝

His wit as sharp as the part of his hair,

His manner ringing warning bells.

“Its all so easy” he begins and then proceeds

Writing down in strange white script,

Original formulae and intricacies,

Into which brave Einstein dipped.

He turns around and amusingly glances

Down in our horrified direction,

As we stutter as if the point

Has not escaped our comprehension.

His wide white smile deals verbal blows,

“Done the problem yet?” he states,

While all the while he really knows

That everyone can’t calculate.

As obvious as it is to him,

Our understanding’s not quite there;

“I’m disappointed” is his whim,

As we all cringe in bleak despair.

And when the hour finally ends,

And all can breathe with quick relief;

He turns and says,”To make amends

“We’re going to have a test next week!”