Systemic Anti‑Black Barriers to Blood Donation in Canada… Part 1

and

Ã˝

June 1, 2023

Ã˝

I have been researching Canadian Blood Services (CBS) for over 20 years, and my doctoral dissertation, , investigated anti-Black homophobia and transphobia in blood donation. I literally have a PhD in the donor protocols used by Canadian Blood Services. Years later, in 2017, I received a to explore Black gay and bisexual men’s experiences with blood donation practices. I have published a .

In this two-part blog, I offer an overview of the systemic anti-Black barriers that have negatively impacted the participation of Black people in blood donation in Canada.

CBS was established in 1998 as a non-governmental not-for-profit entity that would oversee the provision of blood and blood products. CBS is “nationally responsible for a secure system of life essentials for transfusion and transplantation that’s reliable, accessible and sustainable.”[1]

Over 1.2 million people in Canada are Black[2], and those over the ages of 17 (18 in Quebec) are each potentially a viable resource to the nation’s blood supply. I use the term Black to refer to: people of African descent with long standing presence in Canada as well as diasporic experiences, who identify as Afro-Indigenous, African Nova Scotian, Black-Indigenous, Black African, Black Caribbean, Black North American, or multi-racial, and identify with their African ancestry, specifically including Black women and 2SLGBTQIA+ people.

In December 2022, people across Canada, wanting to increase our participation in stem cell and blood donations. However, a simple invitation is not enough to bring us to their clinics — a long and fraught history of anti-Black racism in blood donor protocols and practices created structural barriers that still have an impact today. Here, I provide a timeline of anti-Black and discriminatory donor protocols and practices.

1940s: Racial segregation of donated blood

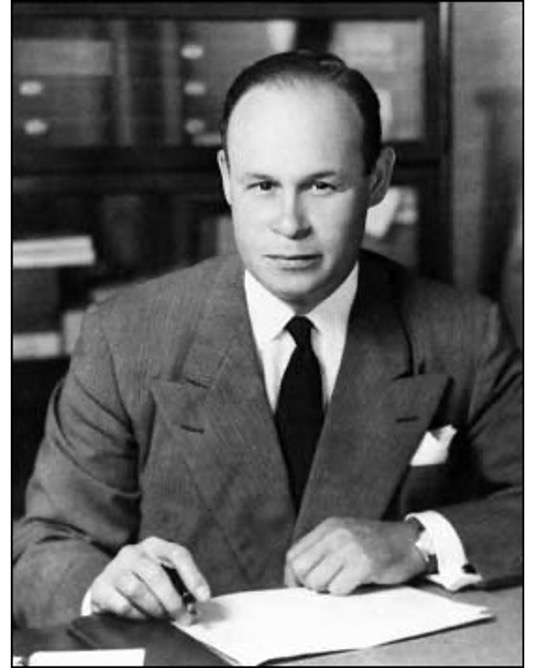

Incorporated in 1909, the Canadian Red Cross Society (CRCS) was an auxiliary to the government’s military medical services in wartime. The CRCS held its first public, non-military blood-donor clinic in 1940. What made this possible was the inventions of , (1904-1950), an African-American cisgender man who was both a surgeon and scientist. Dr. Drew earned the title “” thanks to his technological inventions that allowed for the long-term preservation of blood plasma. His inventions were monumentally transformative and allowed for the creation of national blood collection programs in Canada, the United States, and Britain.

DR. CHARLES DREW,Ã˝Black Inventory Online Museum

With the slogan “Make a Date with a Wounded Soldier,” Canadians were urged to donate blood, and all donations were reserved for use within the military. The first blood transfusion recipients were white American and British soldiers. Following the direction of the American Red Cross Society, all blood collected in Canada and the U.S. was racially catalogued to ensure that white soldiers did not receive blood from not-white [people][3]. As the creator of the modern blood donation system, Dr. Drew, rigorously objected to the practice of the racial segregation of donated blood, correctly stating that there was no scientific evidence to support such a practice. However, CRCS and public health officials insisted on employing this segregation practice.

o.canada.com

o.canada.com

It is important to note here that between 1940 and 1942, women, who largely ran the clinics, were not allowed to donate blood due to the misconception that women could not handle the physical process of donation.

During its tenure of creating, administering, and managing the blood system in Canada, the CRCS had numerous challenges with contaminated blood supplies. In 1962, hepatitis infections had increased drastically, and blood-donor clinics were shut down as a result. Ten years later, hepatitis was also cited as the reason for ending the practice of collecting blood from prisoners, as infection rates were documented as higher within prison population than in the “general public”[4]. It is noteworthy that such exclusions did not stop the hepatitis outbreak. Though infections and contagions (hepatitis, syphilis) within the blood supply were recognized as impossible to prevent, they were (it is argued) important to manage. Yet the tools of blood and donor management were inadequate and wrong-focused; this was due not only to inadequate testing mechanisms, but also with an inability to consider and grasp the discriminatory cultural implications of ‘safe blood’ placed upon identities deemed to have unclean and unsafe blood.

1980s-90s: The AIDS epidemic, the tainted blood crisis, and anti-Black and homophobic stigma

In the 1980s, the CRCS, under increasing pressure from the U.S. Center for Disease Control (and without public consultation), created and released a pamphlet asking people considered to be at “high risk” of getting AIDS to refrain from donating blood. The people they identified would become to be known as the 4Hs – “homosexuals,” Haitian people (regardless of citizenship), heroin drug users, and those with hemophilia. As could be expected, this was rightfully met with outrage from queer communities and Haitian communities and others.

The focus on (perceived) identityÃ˝is not a reliable scientific screening practice.

Even today, there remain stereotypes and stigma on the transmission of HIV.

While there is not enough room in this blog post to delve into the anti-Black homophobia and transphobia embedded in early AIDS research[5], it is important to state that some of this discrimination remains today. Further, respectability politics and moral judgements continue to entrench these stereotypes.

Focusing on identity and not behaviour or activities was a significant cause of the tainted blood crisis.

Preventing specific groups of people from donating bloodÃ˝has never kept the blood supply free of disease or viruses.

. To “protect" the blood supply, North American health officials, including the CRCS banned men who have sex with men from donating blood. They also banned Haitian people, regardless of citizenship. An AIDS diagnosis was attributed to specific types of people, but not to transmission through specific activities such as sex, breast milk, or sharing needles. This may have emerged from the panic of confronting a new epidemic, but equating disease with identity has never been a sound scientific practice. This type of scientific racism can only produce harmful and spurious evidence.

The anti-Blackness and homophobia of early detection included assumptions of a lack of moral correctness and self-control among men who have sex with men and Black people (including Black gay and bisexual men). Sexual morality fueled the stereotypes of this transmission. This was fed into by a puritan belief that sex was only for procreation, and sex for pleasure was lascivious and immoral. For this reason, among others, Black people and men who have sex with men (and Black men who have sex with men) were expected to “‘take ‘ownership’ of and assume ‘responsibility’ for the virus”[6] by not donating blood. This “choice” was presented as the only way to keep the blood supply safe. This focus on identity-based screening practices is both faulty and unscientific.

In 1993, the Canadian government launched the Royal Commission of Inquiry, better known as the , which conducted a public investigation of the Canadian blood system and the tainted blood crisis.

As I have :

The panic regarding HIV/AIDS is conflated with the panic regarding homosexuality and the continuing colonial panic about miscegenation. As has been stated elsewhere, HIV and AIDS is an epidemic on multiple simultaneous levels: it is an epidemic of a transmissible lethal disease as well as an epidemic of meanings or significations.[7] It is in this climate that the Canadian federal government established the Royal Commission of Inquiry on the Blood System in Canada (otherwise known as the Krever Commission) in 1993. The Krever Commission’s report, which was tabled in the House of Commons in 1997, concluded that, although it was inevitable that there would be a blood contamination crisis, this crisis was much larger than it needed to be. Believing that the Canadian Red Cross Society had now become itself too tainted and contaminated from its failures to effectively and properly protect the innocent victims of this blood crisis, the Krever Commission’s report instructed the government to remove the responsibility of the blood supply system from the Red Cross.”

In Part 2, I focus on systemic anti-Black racism/homophobia in blood protocols deployed by Canadian Blood Services from its 1998 inception.

Ã˝

References

[1] Health Canada. (1997). The new Canadian Blood Services and the new blood system. Ottawa, ON: Government of Canada Publications

[2] Statistics Canada. (2019). Diversity of the Black population in Canada: An overview.

[3]Ã˝Dryden, O.,Ã˝& Lenon, S. (Eds.). (2015)Ã˝Disrupting Queer Inclusion: Canadian Homonationalisms and the Politics of Belonging.Ã˝UBC Press.

[4] Picard, A. (1995).Ã˝The Gift of Death: Confronting Canada's Tainted Blood Tragedy. Toronto: Harper Collins

[5] Browning, B. (1998). Infectious rhythm: Metaphors of contagion and the spread of African culture. New York, NY: Routledge; Farmer, P. (1992). AIDS and accusation: Haiti and the geography of blame. Berkeley, University of California Press; Feldman, E., & Bayer, R. (1999). Blood feuds: AIDS, blood, and the politics of medical disaster. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; Nelkin, D. (1999). Cultural Perspectives on Blood. In E. Feldman & R. Bayer (Eds.), Blood feuds: AIDS, blood, and the politics of medical disaster (pp. 273‚Äì291). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; Patton. C. (1990). Inventing AIDS. New York, NY: Routledge; Patton, C. (1993). From nation to family: Containing African AIDS. In H. Abelove, M.A. Barale, & D. M. Halperin (Eds.), The lesbian and gay studies reader (pp. 127‚Äì138). New York, NY: Routledge; Ã˝

[6] Fouron, G. E. (2013). Race, blood, disease and citizenship: the making of the Haitian Americans and the Haitian immigrants into ‘the others’ during the 1980s-1990s AIDS crisis. Identities: global Studies in Culture and Power, 20(6), 705-719.

[7]Ã˝Treichler, P. (1999).Ã˝How to Have Theory in an Epidemic: Cultural Chronicles of AIDS.Ã˝Durham, NC: Duke University Press.