Lawyer and judge, former senator, chief commissioner of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada (TRC), Indigenous advocate, public speaker — The Honourable Murray Sinclair wore many hats over the course of his incredible life.

Monday (Nov. 4) at age 73 reverberated across Canada, with many groups and individual paying tribute to his leadership on Indigenous rights and justice.Ěý

"Murray Sinclair’s journey in advocacy broke barriers and inspired countless individuals to pursue reform and justice with courage and determination," said the .Ěý

Sinclair began his legal career in Manitoba in 1980 with a focus on civil and criminal litigation, Indigenous law and human rights. He was the province’s first, and Canada’s second, Indigenous judge. Sinclair served as co-chair of the Aboriginal Justice Inquiry in Manitoba and as chief commissioner of the .

Sinclair began his legal career in Manitoba in 1980 with a focus on civil and criminal litigation, Indigenous law and human rights. He was the province’s first, and Canada’s second, Indigenous judge. Sinclair served as co-chair of the Aboriginal Justice Inquiry in Manitoba and as chief commissioner of the .

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau referenced Sinclair's work in bringing the injustice of Canada's residential school system to light with the TRC.

"He challenged us to confront the darkest parts of our history — because he believed we could learn from them, and be better for it,"

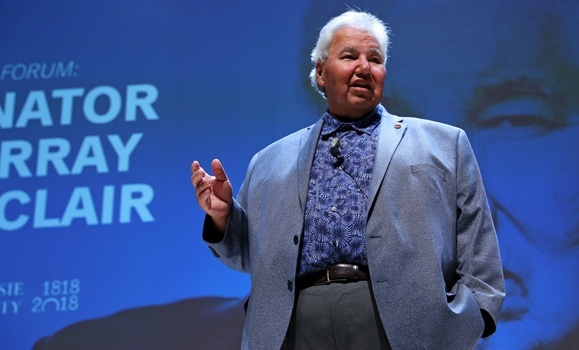

Sinclair, a companion to the Order of Canada who also received an honorary degree from Â鶹´«Ă˝ in 2011, served as a Canadian Senator from 2016-2021. It was during this time in which , a speaker series to mark the university's 200th anniversary in 2018.

Read also: Senator Murray Sinclair urges Canada to think, talk, act differently (Dal News, Sept. 2018)

Dal Magazine sat down with Sinclair during his visit to campus for its Fall 2018 cover story and the following Q&A was initially made available on the magazine's website. We thought it appropriate to republish it in honour of his passing.

Dal Magazine sat down with Sinclair during his visit to campus for its Fall 2018 cover story and the following Q&A was initially made available on the magazine's website. We thought it appropriate to republish it in honour of his passing.

This interview was conducted on September 5, 2018.

What does belonging mean to you?

It’s a question that confounds many of us, because we tend to think belonging just means having membership in a group, or to be part of a group. And it is that, but it’s really about being part of a group where we have a sense of safety, a sense of comfort and a sense of community — that we are able to feel that we are part of something important.

We can belong to groups that don’t give us that sense of importance, [or] we can belong to groups that in fact don’t give us a sense of safety, or a sense of comfort or a sense of care. When you walk into a room, for example, you belong with everyone because you’re all sharing something in common. But that doesn’t necessarily mean that we feel welcome. It’s that sense of welcome, the sense of connection, that sense of cohesion and community — it’s all part of that important issue of belonging.

Why does belonging matter in today’s world?

Why does belonging matter in today’s world?

It’s because as we’re growing up, we have a real need to understand where we come from as individuals and as a community. What is our history as a people? What is my history as a human being? What is the history of my family? Who are my family? Who are my parents? Who are their parents? And to allow me to find out as much as possible who they all were so I know, ultimately, who I am.

But it’s also about, what is our creation story? We all have a creation story. As an Ojibweperson, my creation story is not the same as the creation story in the Bible, for example, but it’s just as valid. And that story in the Bible is just as valid as well. It’s just different. Knowing what our story is, and being able to believe in it, allows me a sense of validation.

And so I belong to those people, and with those people, and there’s a difference between those two contexts. I belong with those people who share that knowledge base and are with me. But it’s not just a question of what I come from but where I’m going. And it’s not just a question of what am I going to do tomorrow, or what am I going to be when I grow up, it’s a question of what happens to me when I die: where does my spirit go? What happens to my body? It’s about sharing knowledge in common, teachings in common, with people who can explain that and help me understand that.

And the third question that comes from all of that is, “Why am I here?” What’s my purpose in life? How am I expected to contribute to this group that I’m a part of? What are their expectations of me and what am I able to contribute to them? That’s part of our learning experience, and our education is about that. So when we are growing up, we develop a sense of what our responsibilities and potentials are, and we are taught how to fulfil those.

And finally, all of that comes together to help us understand the ultimate question, which is “Who am I?” And who are we as human beings? That philosophy comes from elders in my community, but it’s a philosophy as well that comes from the writings of great philosophers like Socrates and Plato and others. Plato writes about the five great questions of life, and they’re very similar questions.

A major theme of the Truth and Reconciliation Report is that the Government of Canada — not just through legislation and government programs but also through the social and institutional processes of society — developed an approach to Indigenous people that required them to be taken from their community, from their sense of self, and to try and make them feel like they belonged to something they knew they didn’t belong to, or to belong to something where they were rejected.

Many Indigenous children that went to residential schools were taught that their people were pagans, heathens, savages, and that they were not worthy of belief, not worthy of being followed — that they could be better human beings if they followed this particular lifestyle, the Christian lifestyle, if they became “civilized.” So terminology was used to drive them into thinking their own people were inadequate. We heard from lots of residential school survivors who talked about the fact that when they would go home and see their parents, they would be embarrassed that their parents couldn’t speak English, or that their parents didn’t understand what they were going through or had the same knowledge base they had. That embarrassment manifested itself in family relationships.

So being taken away from your natural environment and being placed in an institutional environment was the first step of the residential school system. And the process of change might have worked if they had been placed into another family-type environment, if they were placed with people who loved for them and cared for them as if they were their own children. But that didn’t happen in residential schools. They tried to make it happen in the child welfare system, but it was too little, too late. The child welfare system is now seen as something like another form of the residential school system. Therefore, taking children away from their natural environment is now seen as inherently the wrong answer. Taking them away from their parents who are taking care of them might be the safest thing to do, but that doesn’t mean you need to take them away from their community. There should be people in their extended family who can still take care of them, as traditionally was always the case. And then we need some supports in order to do that. That’s really where we should be heading.

When have you most felt like you belonged?

Most of my life, I was raised in an environment in which I was very successful: I was a top student, a very good athlete, and I participated in all of the sports and the teams. I was held in high regard by my teachers. I felt like that was the right thing to do, I felt like I belonged in that path, that that was my future.

But where I lost that sense of belonging is when my children were born. When my first child was born, it made me realize that here I am, holding this Indigenous child, and I don’t know how to help him become an Indigenous man. That’s when I realized that we don’t belong in this kind of life. We need to figure out a way where we can still participate in this day and age but as Indigenous people, as Anishinaabeg people. And so that became my challenge, as a young father. And that’s been my life’s ambition with all of my children, to help them to see how they can live in this day and age and still be true to their identity.

I felt I could do that when I finally found elders who recognized, along with me, the importance of that, and we discussed together about how we could make that happen. And that occurred probably in the 1970s, early 1980s. And it became my ambition as a young lawyer, just around the time I graduated, when I realized there is a space for me and I have to figure out how to make that space fit for me.

What is the single biggest threat to building a belonging society?

It really is from people who don’t want you to belong with a place they belong to — so it’s rejection. The biggest threat to belonging is rejection. And it’s the rejection from people or by people who are determined to protect whatever privilege they hold—that they see you as a threat, that they don’t want you to be part of their group because you don’t look like them, or act like them, or talk like them, or that you represent something which is abhorrent to them.

People have been raised in Canadian society, over many generations, to believe Indigenous people are inferior, and if we don’t act like we are inferior, they see that as a threat. The same with women — men were educated that women are to behave or “belong” in a particular way or role in society, and if they don’t fulfill that role or image, they see that as a threat, that something’s wrong with them for not conforming. When they see people who are transgender, people who are homosexual, people who follow two-spirit way of life, they see that as a basis for rejection because of what they have been raised to believe. So when they reject people, it’s often for a reason that’s invalid — but to them, it seems perfectly valid to do it because they have the support of others within society to do that.

There is a phenomenon at play in society which speaks to the fact that some of us who succeed—and I speak to this from experience — there’s always this question in the back of your head about being a fraud. You feel someone’s going to come along someday and be like, “Ah ha! You don’t really belong here, do you? You’re a fraud! Because you’re an Indigenous guy. Or a woman.” So the imposter syndrome is a real recognized social stigma, and many people live their life fraudulent because they’re trying to belong.

What one change could we make as a society to improve belonging?

We need to educate people — we need to educate children, in particular, because that’s where it starts, but we need to educate all people about the validity of all of these different roles that we play, these different perspectives that we have.

We need to figure out how to adapt to change as change happens around us, because society is never really a stable place. It’s always changing, always evolving. The Canadian society we have today is not the society that was created at the time of Confederation. It’s a different group of people — different groupsof people, with different ways of thinking and believing about this country. So this country has changed. This country has even changed in the past 10 years. And this country will change over the next 10 years. That change will be a constant.

And so we need to get people to understand that change will be constant and be willing to embrace it, to not be afraid of it, and that it’s not necessarily a threat to our existence but that we can manage it.

What can each of us do, right now, to foster belonging?

I think self-awareness is the key. People need to be aware of their own sense of belonging — not just the importance of it, but how it manifests for them. What does it mean for you to belong? How do you see that working for you, and how can you use that knowledge to facilitate the ability of others to belong as well?

The other question that raises is: how do the principles of belonging and uniqueness work together? Do you necessarily have to be the same in order to belong? And the answer to that is no, you don’t. But how can you belong together and still be different? And that’s a conversation we need to have, and an understanding we all need to develop.

One of the reasons racism persists is because people don’t look like us, and because of that we don’t feel that they belong to the same group as us. Racism, or sexism, or ageism, whatever it is that we’re talking about, is really about how we don’t see them as we see ourselves. We need people to understand that not everyone needs to look like us to belong with us.