Repeated blows to the heads of football players can damage the small blood vessels of the brain, according to research by Â鶹´«Ă˝ scientists from the Brain Repair Centre who believe this damage may contribute to brain dysfunction in some athletes years after play has ended.Ěý

The neuroscientists found that the brain's blood vessels can get damaged by a succession of small hits and not necessarily a single, intense blow to the head. Based on their studies in experimental animals they hypothesize that players whose blood vessels don't heal over time may develop long-term inflammation in the brain and a greater risk of future brain dysfunction and degeneration. That can include mobility and emotional issues, and cognitive decline. Ěý

"The outcome of many small injuries that a player had throughout the season and didn't cause significant symptoms may cause damage to small brain vessels," says , a co-author of the study. Ěý

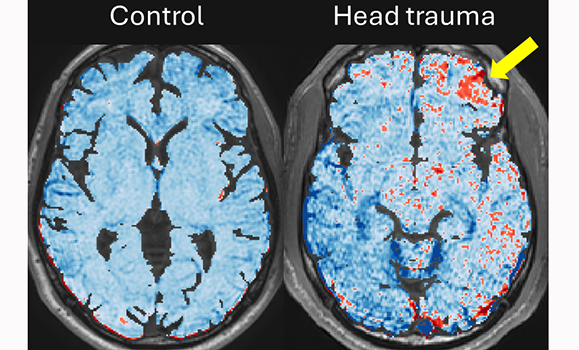

The research centred on the blood-brain barrier (BBB) — the lining of the brain’s blood vessels that blocks harmful substances from entering the brain. When that barrier leaks due to injury (or other diseases), molecules from the blood can seep into the brain and trigger inflammation that can undermine brain function.  Ěý

The study was led by Dr. Friedman, the Dennis Chair of Epilepsy research at Dal's Department of Medical Neuroscience; Dr. David Clarke, chief of Neurosurgery at the Nova Scotia Health Authority; Dr. Casey Jones, resident physician in the Emergency Medicine program at Â鶹´«Ă˝; and, Dr. Lyna Kaminsky, a post-doctoral fellow in Dr. Friedman’s lab. Ěý

Improving player safety

Dr. Jones, a former Â鶹´«Ă˝ Tiger football player and resident physician in Dal's Department of Emergency Medicine, said he was motivated to do the research to find ways to improve player safety.  Ěý

“As someone who’s been involved with football for nearly my whole life, it’s been an honour to collaborate with our players, coaches and staff to drive this novel brain research forward, and to ultimately make the game we all love safer,” he says.  Ěý

“The players have been the true champions of this work, allowing us to do MRIs, bloodwork and other interventions that take a lot of time out of a busy student-athlete’s life.”Ěý

The work, which was funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, involved specialized helmets that were used to monitor head impacts in 60 university football players. The helmets were purchased by Â鶹´«Ă˝ Football in 2019 with help from a projectDal campaign. Five athletes who sustained a concussion during the football season underwent MRI scanning to detect BBB leakage. The leakage was found to be more linked to impacts sustained in all games and practices leading up to the concussion, rather than the last pre-concussion impact.  Ěý

Returning to play

The findings add to the understanding of concussions, while also influencing decisions about when players are safe to return to play. Ěý

"Based on current guidelines, concussed athletes can return to play once their concussion symptoms resolve," says co-author Dr. Kamintsky. "We believe that this is a suboptimal measure of brain health and that neuroimaging stands to provide a more accurate indication of return-to-play safety." Ěý

The authors stress that their research is an observational pilot project, but that the findings suggest it's important to identify players who could be vulnerable to mild head injuries and could develop future complications.  Ěý

"If we can identify them early, then we can treat them before they develop severe complications," says Dr. Friedman. Ěý

Â鶹´«Ă˝ Tigers football players participated in the study.