A NIGHT AT THE COHN is truly a rite of passage for any Halifax arts lover. After all, the stage of the ┬ķČ╣┤½├Į Arts CentreŌĆÖs Rebecca Cohn Auditorium has seen it allŌĆöfrom the perfect pirouettes of the National Ballet of Canada to the thunderous tenor of Luciano Pavarotti; from the anecdotes of Stuart McLean to the activism of Angela Davis; from the first shows of Leonard CohenŌĆÖs acclaimed comeback tour to Gord DownieŌĆÖs final concert before his death. Not to mention the excited footsteps of the thousands of students whoŌĆÖve walked across the stage to receive their Dal degrees.

One thing the Cohn hadnŌĆÖt seen yet: Music student Raquel Wasson.

In fact, despite being from nearby Fall River, Nova Scotia, Wasson was unfamiliar with the ┬ķČ╣┤½├Į Arts Centre when she was growing up. Though she had a musical disposition, her focus in high school was on her plans to study nursing. At the last minute, she instead decided to pursue her passion for percussion and piano. It wasnŌĆÖt until she arrived on campus to explore ┬ķČ╣┤½├Į that she got her first glimpse inside DalŌĆÖs home for the performing arts.

ŌĆ£My first impression was that it had a charming ŌĆÖ70s vibe,ŌĆØ she says. ŌĆ£The whole purple carpet, the Sculpture CourtŌĆ” I kind of liked the vintage aesthetic of it.ŌĆØ

SheŌĆÖs not wrong about the era. The ┬ķČ╣┤½├Į Arts Centre first opened its doors in 1971, fifty years ago this year, part of an unprecedented building boom in ┬ķČ╣┤½├ĮŌĆÖs history to that point. Its two construction contemporaries from that same year, the Killam Memorial Library and the Life Sciences Centre, share a few things in common with the Arts Centre beyond their moment of origin, most notably their Brutalist designŌĆöa sometimes loved and oft-scorned architectural marker of their era.

But possibly their strongest common bond is the part they played in reshaping DalŌĆÖs relationships with its broader community. Perhaps ironically, the story of these imposing concrete structures is one about ┬ķČ╣┤½├Į becoming more open, to more people, than ever before.

IN THE HISTORY of Canadian higher education, few transformations have been as dramatic as the post-war boom. Not only did CanadaŌĆÖs university-aged population nearly double in the immediate decades after the Second World War, the percentage of them who chose to attend university grew even more dramatically. At ┬ķČ╣┤½├Į alone, enrolment more than quadrupled in 20 yearsŌĆöfrom about 1,500 students in 1950 to more than 6,600 in 1970. New universities were forged from nothing to meet the skyrocketing demand, while legacy institutions were forced to frantically scrape together what capital they could to construct new buildings at an unheard-of pace.

┬ķČ╣┤½├Į, with nearly 150 years of history by that point, fell decidedly into the legacy category. The physical campus, built for a much smaller student body, was practically bursting at the seams. Under the leadership of ambitious president Henry Hicks, ┬ķČ╣┤½├Į launched a building boom to match the baby boom that necessitated it: seven significant new buildings funded and built in a 20-year span, including among them the Tupper Medical Building, the Weldon Law Building, the Student Union Building and Dalplex.

The three buildings that made up that eraŌĆÖs ŌĆ£Class of ŌĆÖ71ŌĆØŌĆöthe Arts Centre, Killam Library and Life Sciences CentreŌĆöhave similar origin stories, but each with its own twist. With the Life Sciences Centre, ┬ķČ╣┤½├ĮŌĆÖs vision of a unified home for the psychology, biology and oceanography departments was propelled forward, in part, by funding for an advanced new saltwater research facility. Meanwhile, donor generosity was the impetus for what became the ┬ķČ╣┤½├Į Arts Centre. The executors of the will of Rebecca Cohn, a Polish immigrant whose fortune was made in Halifax real estate, had suggested her 1962 bequest to the university should be used for a performance auditorium. But it would take several years and another giftŌĆöthis one from future chancellor Lady Dunn, for a theatre in her late husbandŌĆÖs honourŌĆöto realize the full vision for a proper arts centre.

Killam Library

The Killam Library, meanwhile, was born of a mix of both organizational and donor imperative. ┬ķČ╣┤½├Į had quickly outgrown the Macdonald Memorial Library, with both its stacks and reading room crowded beyond capacity and the universityŌĆÖs academic reputation at risk without more space for new acquisitions. But the drive towardŌĆöand the naming ofŌĆöa new library would take a near-deathbed conversation between Hicks and one of ┬ķČ╣┤½├ĮŌĆÖs greatest philanthropists to truly get underway.

IN 1965, Dorothy Killam was in the process of planning what would become perhaps the most significant gift Canadian higher education would ever receive: nearly $100 million to create the Killam Trusts. As the leading university in her late husband IzaakŌĆÖs home province, ┬ķČ╣┤½├Į was not only one of the five schools named as Killam institutions, it would receive the largest share of the funds.

Yet Dorothy also wished to establish another physical monument in tribute to Izaak, in concert with her donation to create the IWK (Izaak Walton Killam) ChildrenŌĆÖs Hospital. In late July 1965, she spoke with President Hicks, who suggested a new library as ┬ķČ╣┤½├ĮŌĆÖs greatest need at that point. Dorothy began the process of updating her will but ran out of timeŌĆöshe passed away only five days later. But Hicks and university leadership were determined to ensure that some of the Killam gift was used to follow through on that final request.

Construction on the Killam Memorial Library began in 1966. Its architect was Leslie Fairn, but a great deal of the vision was owed to new University Librarian Louis Vagianos. ŌĆ£Make the library serve the students,ŌĆØ was his thinking, and it drove the move toward a structure that was, for its time, designed for maximum flexibility while exemplifying modern architectural and decorating features. After construction delays, it was officially opened with a ceremony in March 1971. It remains the largest academic library in Atlantic Canada to this day.

Librarian Karen Smith has worked in the Killam since 1977, arriving when it was still a relatively new building. She still recalls fondly the custom-built rosewood fixings, the efforts to grow the collection into the available stack space, the beloved Special Collections reading series, and the general enthusiasm for what the building meant for ┬ķČ╣┤½├Į and the community.

ŌĆ£ItŌĆÖs the hub of social science and humanities research in the region, quite frankly,ŌĆØ she says. ŌĆ£And over time itŌĆÖs adjusted to peopleŌĆÖs needs in an almost organic way. It can be reconfigured, and has been reconfigured, almost on a dime. The building itself is endlessly flexible as we listen to what the students, in particular, are looking for.ŌĆØ

Students study on the fourth floor of the Killam Library

Indeed, though the buildingŌĆÖs rigid exterior looks much as it did 50 years ago, inside the Killam much has changed. The academic departments that originally found temporary homes in its unfilled stacks have all moved elsewhere, while academic support units like Student Affairs, the Centre for Learning and Teaching, and Information Technology Services have moved in. Special CollectionsŌĆönow the University Archives and Special CollectionsŌĆöhas called nearly every floor of the building home at one point or another. The first floor has now been reconfigured to focus on learning commons spaces to meet the needs of a modern, tech-powered student body. And then thereŌĆÖs perhaps the most significant change of all: the closing of the open courtyard that was a hallmark feature of the building. A glass roof was added in 1996, turning the weather-worn stone atrium into an interior space for meeting, dining and coffee breaks.

ŌĆ£Louis [Vagianos] was Greek and had this vision for a Greek courtyard, which ultimately didnŌĆÖt work as well on the shores of the North Atlantic,ŌĆØ says Sarah Stevenson, who has worked with ┬ķČ╣┤½├Į Libraries for 20 years and is currently head of the Killam. She says the library has changed, in no small part, because students have changed.

ŌĆ£WeŌĆÖre seeing more foot traffic than ever, but theyŌĆÖre not asking the same sort of questions at the reference desk,ŌĆØ she says as an example. ŌĆ£Google has a lot to do with that. Wikipedia has a lot to do with that. So the requests weŌĆÖre getting now are a lot more difficult and complex.ŌĆØ

Other changes are based on a desire for more open hours, more collaborative and tech-rich learning spaces, and improved accessibility. And, perhaps most tellingly of changing eras, what was once one of the go-to smoking destinations on campus is now smoke-free (like all Dal buildings).

ŌĆ£The idea that you could smoke in the library is pretty funny now,ŌĆØ laughs Stevenson.

WHILE THE KILLAM Library represented the progression of ┬ķČ╣┤½├Į eastward down what is now University Avenue, the Life Sciences Centre was an infill building, one that had to fit around a neighbouring building at the west end of campus. Designed by Ray Affleck of the Montreal firm Affleck Desbarats, it was laid out with each of its primary occupantsŌĆöthe Departments of Biology, Oceanography and PsychologyŌĆöhaving a wing of their own, with a suite of shared university classrooms in between. Its interior was equal parts utilitarian and labyrinthine, a layout akin to a real-life psychology experiment for the generations of students tasked with navigating its halls (and, according to rumours, even a possible ghost in the psychology wing).

The Life Sciences Centre is home to multiple departments

But when it opened its doors just in time for the fall 1971 term, the new Life Sciences Centre (or LSC, as it is commonly known) contained some of the most unique facilities in Atlantic CanadaŌĆöspaces that not only made it a destination for researchers across disciplines, but for generations of school kids on field trips ready to be inspired by the possibilities of science. A great deal of the buildingŌĆÖs design and mechanical systems supported the AquatronŌĆöthe regionŌĆÖs largest university aquatic research facility and a world leader in the field. With the ability to transport salt water straight up from the HalifaxŌĆÖs Northwest Arm, its tanks have hosted countless types of saltwater and freshwater species and hundreds of complex oceanographic and aquatic experiments over the years. Other popular school tour destinations have included the eighth-floor greenhouse or the Thomas McCulloch Museum on the third floor, featuring the naturalist collection of ┬ķČ╣┤½├ĮŌĆÖs first president.

A less likely tour stop: the buildingŌĆÖs nuclear reactor. Yes, beginning in 1976, the basement of the LSC hosted the SLOWPOKE reactor, short for ŌĆ£Safe Low Power Critical Experiment.ŌĆØ It was decommissioned in 2011 after 35 years of safe, successful research use. The room where it was located is now includes a drill core lab space used by Professor Grant Wach and other faculty for teaching and research. Dr.ŌĆ»Wach, an earth scientist and director of the Basin and Reservoir Lab, has been a resident of the LSC since 2000; he notes his Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences, then called the Department of Geology, was only added to the building as an afterthought. He admits the building is not without its confusing charms.

ŌĆ£You say to someone, ŌĆśIŌĆÖll meet you on the ground floor.ŌĆÖ Well, there are three ground floorsŌĆöbecause it was built on a hill!ŌĆØ he explains.

The unusual layout of the Life Sciences Centre has confused generations of students.

His personal hope for the future of the LSC is for the university to build on displays like the McCullough Museum, by including touch tanks, rock cabinets and photo displays to make the space even more open to the community ŌĆö a living museum of sorts, inspiring not only the buildingŌĆÖs residents but groups of future young scientists.

ŌĆ£We have this amazing scientific community here, and we can do even more to put its great work on display and encourage the next generation of scientists to come to Dal.ŌĆØ

COMMUNITY HAS BEEN at the heart of the mission of the ┬ķČ╣┤½├Į Arts Centre from its very beginning. After ┬ķČ╣┤½├ĮŌĆÖs leaders struggled for a vision of how artistic performance could fit into the universityŌĆÖs mission, the model for the Arts Centre as both a home for DalŌĆÖs programs in music and theatre, as well as a destination for performers and artists, took shape. Hicks envisioned it as a ŌĆ£lighthouseŌĆØ for the Halifax community, attracting all sorts and tastes, and would later describe it as one of his greatest achievements. Designed by the architecture firm C. A. E. Fowler & Company, the Arts Centre included the 1000-seat Rebecca Cohn Auditorium along with the smaller Sir James Dunn Theatre for live theatrical performances, practice and rehearsal spaces for students, classrooms and offices, an open Sculpture Court for gathering and performance, and a permanent home for the ┬ķČ╣┤½├Į Art Gallery.

The ┬ķČ╣┤½├Į Art Gallery has welcomed thousands into its space.

ŌĆ£IŌĆÖve always loved how the buildingŌĆÖs design is different from classic Brutalism [and its] concrete block buildings with little detail,ŌĆØ says Peter Dykhuis, the ┬ķČ╣┤½├Į Art GalleryŌĆÖs director. ŌĆ£But this one has all these curves and these textures and these allusions to musical instruments and seashells and all of this. ItŌĆÖs like poetic Brutalism.ŌĆØ

The construction was slow and problematic. A leaky roof, changes to auditorium capacity and disputes over furnishing all delayed completion. But the Rebecca Cohn was able to host its first official performance in January 1971, featuring cellist Gary Karr and the Atlantic Symphony Orchestra, followed by an official opening for the Arts Centre in November of that same year with a week of cultural events and a special convocation presenting honorary degrees to several leaders in CanadaŌĆÖs arts community.

The impact to the cityŌĆÖs arts was enormous and near-immediate. The Atlantic Symphony Orchestra, for one, had a home, to be succeeded by Symphony Nova Scotia, which performs to thousands of people in the Cohn to this day. Bookings in the Cohn proved broad in genre and taste, and within five years the venue was hosting 65 shows a year and growing, with an estimated seven per cent of the Halifax population going to the Arts Centre at some time each year.

ŌĆ£ItŌĆÖs really the only theatre of its type and size in the region,ŌĆØ says Shirley Third-Genus, the Arts CentreŌĆÖs current executive director. ŌĆ£It serves our community, both ┬ķČ╣┤½├Į and the broader community. And it does it all very well. ItŌĆÖs a fully professional theatre with incredible technicians, incredible equipment. ItŌĆÖs an all-around exceptional facility in a city of this size.ŌĆØ

Third-Genus credits, in part, the diversity of bookings for making the Arts Centre such a successful venue. From big lectures like Dal 200ŌĆÖs Belong Forums and the Stanfield Conversations, all the way to rock concerts, comedians and even the construction of a squash court on the stage, the Cohn has proven incredibly versatile over the years.

ŌĆ£ThereŌĆÖs not many events you really couldnŌĆÖt put on in the CohnŌĆömaybe diving,ŌĆØ says Colin Richardson, the venueŌĆÖs technical director. ŌĆ£Everyone who works at the Cohn has a dedication to excellence. This is the pinnacle. If you live in this area, you want to work at the Rebecca Cohn, and once youŌĆÖre here youŌĆÖre part of a team that wonŌĆÖt accept anything less than excellence. ThatŌĆÖs just what we do.ŌĆØ

EVEN THE MOST imposing structures are full of change ŌĆö especially when there are new generations of students, staff and faculty to support.

In the case of the Life Sciences Centre, a multi-year, multi-million-dollar retrofit earlier this decade has made dramatic improvements to the buildingŌĆÖs interior infrastructure systems and environmental footprint, while the addition of the Wallace McCain Learning Commons, opened in 2015, has created a new student hub. Meanwhile, in the Killam, some of the more recent changes have focused on reconciliation efforts, including the launch of the Gord Downie and Chanie Wenjack Legacy Space and development of an Indigenous Community Room comparable to one that exists on DalŌĆÖs Truro Campus.

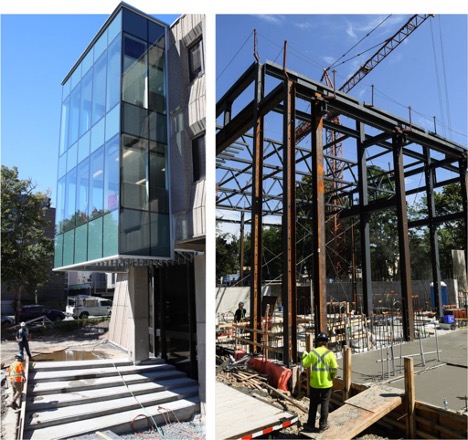

But the biggest transformation among the three buildings marking 50 years this year is currently underway in the ┬ķČ╣┤½├Į Arts Centre. In Fall 2019, construction began on a $38.5 million expansion that will add a three-story performing arts wing featuring new practice rooms, a rehearsal studio, space for DalŌĆÖs Costume Studies program and a 300-seat concert hall named in honor of Joseph Strug, son of Holocaust survivor and business leader, Morris Strug.

Work in progress on the $38.5 million ┬ķČ╣┤½├Į Arts Centre revitalization project. (Photo: Danny Abriel)

ŌĆ£This will be life changing for our students,ŌĆØ says Jerome Blais, director of the Fountain School of Performing Arts. ŌĆ£More broadly, the Fountain School is already a very important partner in the cultural life of Halifax and the Arts Centre is already a hub, but with this new equipment and space, I think weŌĆÖll be able to go even further in having the Fountain School as a major player in the artistic life of Halifax and Atlantic Canada, bringing people together.ŌĆØ

With the help of donor contributions to the Fill the House campaign, as well as funding from the provincial government and others, the Arts Centre expansion is set to open next year. For student Raquel Wasson, it canŌĆÖt come soon enough.

ŌĆ£This past year has been really difficult for everyone, being away from the Arts Centre [during COVID],ŌĆØ she says. ŌĆ£To be back and seeing all the changes is really exciting.ŌĆØ

BRUTAL DESIGNSEmerging from the mid-century modernist movement, Brutalism is a term derived from the French for ŌĆ£raw concreteŌĆØ (ŌĆ£b├®ton brutŌĆØ)ŌĆöa style defined by unadorned concrete, strong geometric structures and freestanding sculptural forms set in tightly integrated landscapes. This ŌĆ£rough and readyŌĆØ style, as Dal Architecture Professor Christine Macy refers to it, caught the imagination of architects in Europe as they sought cheap, efficient materials to meet the urgent demand to rebuild housing after the Second World War. |

This story appeared in the DAL Magazine Fall 2021 issue. Flip through the rest of the Fall 2021 issue using the links below.